Latest News

Global communication network concept.

It is not easy to build a successful Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite constellation. Aside from the technical and regulatory challenges, there are many business and financing issues as well. These issues have already caused LeoSat to fold, sent OneWeb into Chapter 11 and kept Telesat in announcement mode for over three years now. Let’s dig deeper into these issues and find out how some operators are trying to manage them.

Customer or Investor – The Impossible Choice

One would think that a business case with ROIs that exceed those of Direct-to-Home (DTH) broadcasting from Geostationary Orbit (GEO), and backed by more than $2 billion in customer commitments – something that LeoSat announced in the summer of 2019 – would give investors enough enthusiasm to comfortably put their money behind the project. Wrong. No matter how attractive the ROIs, if investors have to part with their money for 10 to 12 years, there’s a problem. It blocks access to a large portion of investors that would rather accept half the ROI for projects lasting half as long. This ultimately yields the same results with less risk.

An effective remedy to this problem is to play the philanthropy card. Attracting investors with a plan to launch satellites that target rural and underprivileged communities with a promise to bring them online and provide equal access and opportunities is a strategy that worked well for O3b and OneWeb. The business case for these type satellite constellations, however, is far from solid. A revenue strategy that is dependent on the purchasing power of rural and underprivileged communities, is asking for problems. But both companies dodged the bullet — O3b was absorbed by SES, safely cushioned in a steady DTH revenue stream, and OneWeb has been bought out of bankruptcy by the United Kingdom. Although the deal with the U.K. saved OneWeb, additional revenue streams still need to be developed to ensure even basic viability.

So, it seems that either you have a great business case but no access to money, or you have access to money with a flawed business case. Neither will work. While marrying the two variants into a profitable business case with philanthropic aspects seems to be the obvious way out, the different companies are trying other alternatives.

LEO as an App

Almost six years ago when Elon Musk addressed SpaceX employees to celebrate the company’s new office in Seattle, Musk said he expected more than half of Starlink’s traffic to be long distance, and he gave an example of how routing data from Seattle to South Africa would be much faster through his satellites than via fiber. This clearly suggested the use of intersatellite links (ISLs), but apart from a few tests, these have not been installed on Starlink. In fairness, Musk also said he expected to launch new versions of his constellation every five years, so it may well be that on his next batch of 4,000+ satellites for 2025 (wow!), the required ISLs will be available. He also compared his constellation to PCs as they are easy to replace, making it possible to test less and launch quicker. So, while he delivered on his promise to launch in the 2019-2020 timeframe, it seems that less testing and design concessions have been required to achieve that goal. That is an unconventional approach but as one can see on the YouTube video, Musk seemed quite comfortable with it.

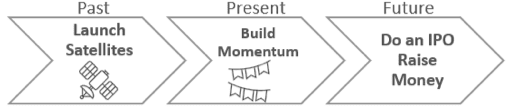

Launching a constellation this way reminds me of how app developers launch new products. They try to get version 1.0 out quickly, such to start building a customer base ahead of the competition and use the momentum and customer feedback to put out bug fixes and new releases, while further increasing their installed base. It is all about timing and building momentum. With many satellites still to launch, Starlink/SpaceX have additional financing requirements in the future and building momentum and customer enthusiasm is an important ingredient to success. After all, when it is about raising money, Uber has already successfully demonstrated that in lieu of revenues and profits, capital markets are perfectly fine accepting customer enthusiasm and market momentum. Similar enthusiasm and momentum around Starlink’s launches will go a long way toward raising the additional funds needed and Musk has already hinted at a Starlink IPO in the future.

Launching a constellation this way reminds me of how app developers launch new products. They try to get version 1.0 out quickly, such to start building a customer base ahead of the competition and use the momentum and customer feedback to put out bug fixes and new releases, while further increasing their installed base. It is all about timing and building momentum. With many satellites still to launch, Starlink/SpaceX have additional financing requirements in the future and building momentum and customer enthusiasm is an important ingredient to success. After all, when it is about raising money, Uber has already successfully demonstrated that in lieu of revenues and profits, capital markets are perfectly fine accepting customer enthusiasm and market momentum. Similar enthusiasm and momentum around Starlink’s launches will go a long way toward raising the additional funds needed and Musk has already hinted at a Starlink IPO in the future.

Another company that seems to be warming up to this approach is OneWeb. The company is clearly trying to build momentum by speculating about offering new GPS type services and announcing that launches will continue in December. It is also clear that the $1 billion that got them out of Chapter 11 will only keep them going for so long, and new funding may be required during the course of next year.

Raising money after an initial launch seems somewhat of an upside-down business model. Some may find that a little unsettling, reckless even, but many will argue that it is a smart, calculated risk. As enthusiasm for space builds, it makes good business sense to get in early to be in the best position for upcoming opportunities.

LEO as an App

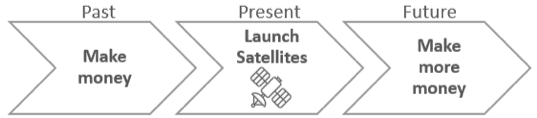

Using satellites as a means to an end, as a tool in service of a higher goal, is the bedrock of our industry. Following on this, a new, steroid business model has been introduced where the higher goal is all about the money.

When the first satellites were launched in the 1960s, it was not about money, it was about pushing the boundaries of technology. When Intelsat – the first satellite operator – was set up as an intergovernmental organization in 1964, its primary focus was not on making money, but to be the vehicle through which participating countries could grow their economies and increase their GDP. To this day there are many national and military satellite systems where it is not about the profits, but rather the data and information produced by these satellites.

Now enter Amazon, which reported $280 billion dollars in revenues for 2019. While normal satellite companies are struggling to raise capital, Amazon can simply use a week’s revenues to build and launch an entire LEO constellation. This is exactly what the company plans to do with Project Kuiper. When ready, Amazon will own a network through which literally everyone on Earth has access to Amazon’s webshop and through which global businesses can send data to Amazon Web Services (AWS) data centers safely and securely.

If the resulting increase in revenues is as little as a few percent, the investment will be paid for within matter of months. Starlink recently announced to develop monthly plans for internet access, starting at $99/month. Something tells me that Amazon is not going to even bother with that. The company may well offer its services as part of a packaged deal for free. When that happens, it’s back to the drawing board for all other LEO operators to rewrite their business plans.

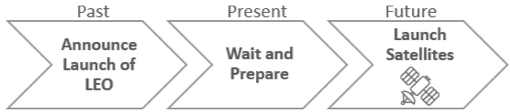

LEO as a Patience Tester

Canadian Telesat put in its application for LEO spectrum early February 2015. The first early bird was ordered well over a year later in May 2016 and launched in January 2018, again well over a year later. Those are big brackets of time, and since then nearly three years have passed without any further launches, satellite orders or vendor announcements. Clearly our patience is being tested. Other startups have taken a similar approach: LaserLight announced its constellation as early as 2012, and despite several press releases on partnerships and a patent, no launches have been scheduled as of yet. The same is true for Kleoconnect out of Germany and various Chinese LEO ventures that may have launched one or two early birds, but have yet to announce the launch of the first satellite in the constellation.

For those that now want to dismiss these companies as failing because they can’t execute their plans … Not so fast! There is another perfectly acceptable explanation. For that to make sense, we need to take a look at Viasat. Known for being a GEO shop and on the record for downplaying the advantages of LEO, Viasat recently announced a venture into LEO after all. In a letter to shareholders, Viasat announced that its LEO constellation will be optimized for the U.S. government’s Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF). To the trained ear, this sounds like the whole thing is conditioned upon getting the required funds out of RDOF. No funds? No LEO!

Announcing plans to launch a constellation early and to then prepare the organization for immediate execution when the right funds are available, is not a bad strategy. Particularly in the context of the recent failures in the industry, it pays off to be prudent. Successful positioning and carefully timing activities is important and will go a long way towards achieving success.

With the billions of dollars going around, we can all agree that LEO is happening. Traditional approaches to launching a LEO business have failed and new strategies are now in play. In casino terms: Starlink and OneWeb are rolling the dice on future money becoming available. Amazon, with its deep pockets, is feeling lucky and is placing big bets on the big boys’ table, while Telesat, ViaSat, and others are sitting on their casino tokens, ready to place their bets when the opportunity is right. Rien ne va plus!

Ronald van der Breggen is an independent consultant at Route 206, helping technology companies become commercially successful. His latest achievement was securing over $2 billion in customer commitments for LeoSat. Ronald holds a business degree from Nijenrode Business University and a master’s degree from Delft University of Technology, both in the Netherlands.

Ronald van der Breggen is an independent consultant at Route 206, helping technology companies become commercially successful. His latest achievement was securing over $2 billion in customer commitments for LeoSat. Ronald holds a business degree from Nijenrode Business University and a master’s degree from Delft University of Technology, both in the Netherlands.

Get the latest Via Satellite news!

Subscribe Now