Latest News

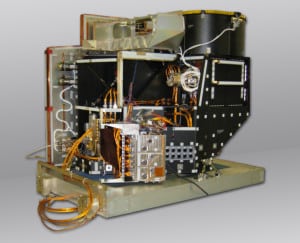

[Via Satellite 04-14-2014] With an impending gap in meteorological satellite coverage looming over the United States, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is being pushed to make greater use of commercial data sources. On April 2, 2014 the House of Representatives passed the Weather Forecasting Improvement Act, which strongly encouraged the agency to make better use of private and academic sources. Opportunely, Exelis is working in partnership with GeoMetWatch on a hyperspectral sounder. The device pools together what the company learned from manufacturing Advanced Baseline Imagers (ABIs), and is designed to operate as a hosted payload in geostationary orbit.

Sounders differ from imagers in that they don’t provide pictures of cloud cover or the Earth’s surface. Instead they take a vertical profile from orbit and record layers of atmospheric activity. This information is fed into models to create more accurate predictions.

“The idea with the geostationary hyperspectral sounder is you will get persistent coverage of tornados, of hurricanes and of severe weather 24 hours a day,” Eric Webster, VP of Exelis Geospatial Systems told Via Satellite. “The goal would be to improve forecast lead times of things like tornadoes significantly, from 12 minutes to 40 minutes. That’s the kind of ability it gives to know about severe storms and what is occurring in the atmosphere.”

Exelis has regularly built imagers and sounders for meteorological purposes. The company is currently contracted to build four ABI units for U.S. agencies, two for Japan and another for South Korea. But hyperspectral sounders are different from imagers and other previous instruments because of the sheer volume of data they create.

“Exelis currently builds the sounders that are orbiting today in geostationary orbit,” explained Webster. “They have 19 channels, meaning 19 slices of the atmosphere above the United States and adjacent oceans. A hyperspectral sounder would give you 1,300 slices. You get much more definition of what is happening at each individual level of the atmosphere.”

The U.S. National Weather Service desired to have this technology over a decade ago, but NOAA opted against it. The order of magnitude more data was something the agency did not anticipate being able to handle without a much more sophisticated — and cost-prohibitive — ground system. At the time ITT, now Exelis, continued to research the project, and now the company believes it can bring geo-hyperspectral sounders to orbit.

“Through advances in algorithms, computing power and other things I think there is a strong belief that the ability to process the data does not need a whole new ground system,” said Webster.

GeoMetWatch declined to comment on the company’s new agreement with Exelis. The company is partially funding Exelis to help finalize the design of the instrument centered around the ABI NOAA originally desired for the GOES R mission. The GeoMetWatch design was based on a NASA instrument at Utah State University, but that project fell apart after funding proved difficult to acquire. Exelis does not expect the same hurdles.

“What we’ve been working on with GeoMetWatch is study-funding to finalize the design of the instrument, but given that we are on contract to build seven ABIs, we plan to reuse more than 80 percent of the instrument,” said Webster. “So from a cost perspective we are pretty comfortable with what the costs are going to be with a small amount of nonrecurring. We are working with GeoMetWatch now to further define what that design will be, and then what those minimal differences will be between what we are building and what we would have to build for the hyperspectral sounder.”

Still, it is up to GeoMetWatch to find satellites that can support its hosted payload. The original plan was to launch with the SSL-built AsiaSat 9 in 2017. It is not entirely clear what the new timeline will be for GeoMetWatch going forward.

“[Exelis] can build a geostationary imager in about three years, and we believe we could also build a geo–hyperspectral sounder in about that time,” said Webster. “We are working to see if we can shorten it to earlier than three years. It probably takes about six to 12 months depending for integration on a satellite. So hopefully within three to three and a half years we can build and launch one of these instruments provided we have the proper customers and funding.”

Get the latest Via Satellite news!

Subscribe Now