Latest News

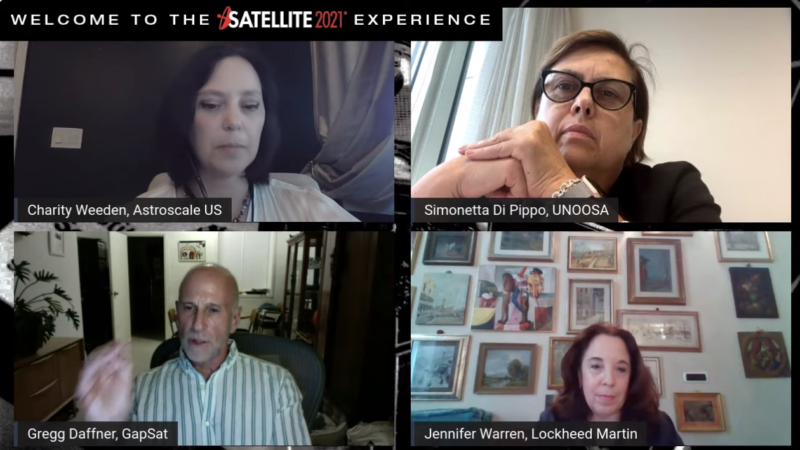

Clockwise from top left: Charity Weeden, Astroscale; Simonetta Di Pippo, UNOOSA; Jennifer Warren, Lockheed Martin; and Gregg Daffner, APSCC. Screenshot from SATELLITE 2021.

Space traffic management, space debris, long-term sustainability, spectrum allocation, Moon resources — the list of challenges for the space policy realm is great. And space is a global resource, so decisions have to be made with stakeholders from around the world, many times with conflicting agendas.

Space policy experts spoke virtually on Monday as part of the SATELLITE 2021 Digital Encore, about how multilateral policy-making can support the growth of space activities.

Gregg Daffner, CEO and president of GapSat and the Asia Pacific Satellite Communications Council (APSCC), sees plenty of room for improvement in multilateral space policy. He detailed some of the gaps in the current systems.

Although the Outer Space Treaty bans certain activities in space, the United States legalized space mining in 2015, and other countries have moved to follow suit. The International Telecommunications Union (ITU), the principle body that regulates satellite communication activities, has no tools to enforce its policies and decisions, and its own members often do not set their policies or regulations in accordance with the ITU frameworks.

“Countries that have waged battles at World Radio Conferences, they’ve lost their arguments, and the conference has adopted decisions that are contrary to what they are looking to achieve. These countries go home and implement the regulations that the WRC has just rejected,” Daffner said. “It’s a mixed up, crazy world out there.”

Jennifer Warren, vice president of Tech Policy & Regulation and Government Affairs for Lockheed Martin, sees a knowledge gap between the commercial sector and regulatory bodies, who may not be embedded in the space industry and understand its issues.

“The business and technical realities, all that expertise resides within the commercial business community. For policymakers to be truly informed in decision making, they need to be partners with the industry that’s going to be regulated,” Warren said. “It has to actually be a stronger partnership. That kind of multi-stakeholder partnership is really important.”

And the orbital environment is growing more complex with Non-Geostationary Orbit (NGSO) constellations, leading to more challenges with spectrum management. Daffner expects that any interference regime put in place by the Western world will be put to the test by Chinese NGSO systems that will look to use the same spectrum.

Daffner said that he believes the Geostationary Orbit (GEO) operators have made spectrum coordination more complex than necessary to protect themselves from competition, and this has come at the expense of bridging the digital divide. He now sees the same playing out among NGSO constellations.

“When these non-GEO constellations were first announced, their talk was all about connecting the other 3 billion people in the world. But as we’ve seen over the last several years, the conversation has now shifted to serving large commercial enterprises, governments, and the military — not creating the kind of digital divide solutions that we’ve been hoping for. This is very disappointing,” Daffner said.

Simonetta Di Pippo, director of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), says there has been confusion about her office’s role and how the United Nations plays a role in space policy making, but space policy will soon take a larger spot on the global stage.

She expects space activities to be one of the main pillars of the United Nations General Assembly in September 2023.

“For the first time in history, there will be quite a huge place or positioning of outer space, and the Office for outer space affairs in the process,” Di Pippo said. “What we have to do is to start with a multi-stakeholder dialogue to define space traffic management and global governance of space activities. This is quite an important goal and an important challenge.”

Looking 30 years into the future, Warren sees a future framework for policy decisions for space that is “multi-stakeholder.”

“[It’s] a setting where you have not just space-faring nations, but space-benefiting nations,” she said. “So, that table where civil society, industry, academia, governments are present, and governments from all regions completely agree. All of that needs to happen if we’re setting the stage for national enabling regulations and national alignments.”

Get the latest Via Satellite news!

Subscribe Now