Lockheed Martin on Cutting Costs with Virtual Reality

A Lockheed Martin engineer manipulates components in VR. Photo: Lockheed Martin.

Lockheed Martin is saving $10 million a year by implementing Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR, AR) tools in the production line of its space assets. “And a lot of folks would say that’s a conservative estimate, including myself,” Darin Bolthouse, engineering manager at Lockheed Martin, said in an interview with Via Satellite.

Bolthouse, who heads up the company’s Collaborative Human Immersive Laboratory (CHIL), mentioned that it cost just $5 million to set up the lab back in 2010, and so the company has seen a significant (and continually increasing) return on its original investment.

Lockheed Martin first toyed with the idea of VR during the development phase of the F-22 and F-35 programs at its lab in Fort Worth, Texas. “In those cases they were focused on maintenance applications,” Bolthouse said. Since then, the company has expanded those same tools and techniques to nearly all of its initial product, tooling and facility designs.

Specifically, Lockheed Martin uses 3D imaging in VR to catch engineering missteps before the asset hits the production floor, saving time and money by correcting those errors sooner rather than later. It also helps accommodate for human factors, Bolthouse said, such as ensuring a particular component can be reached by hand. “The whole goal is to reduce any mistakes … That way when you do it for real on the shop floor, you’ve optimized what it is you’re trying to do,” he said. That’s the bulk of where the [savings] estimate comes from.”

Before 2010, in order to do a thorough design review Lockheed engineers would have to build and handle a physical prototype. But that, of course, costs time and money. Streamlining that process was one of CHIL’s primary objectives at its inception. For Bolthouse, bringing that work into a VR environment seemed like the logical next step. “One thing to understand is this is an extension of doing design review with Computer-Aided Design (CAD) tools,” Bolthouse said, pointing out that engineers have evolved from sketching on a drafting board to constructing 3D models on the computer. “We’ve got this wealth of 3D data already out there … The ability to bring that into an immersive VR environment allows our engineers to see that in full scale,” he said.

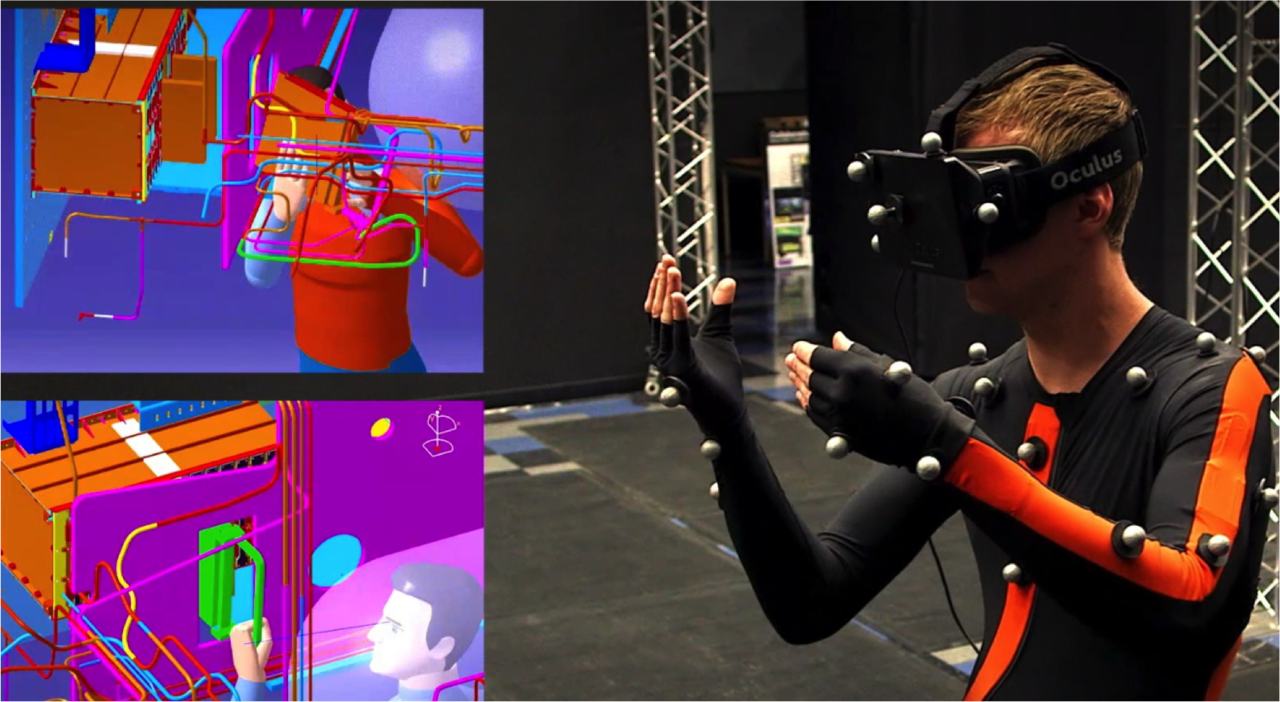

CHIL features two distinct technologies. Engineers can step into the Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE), where they can manipulate full-scale, 3D models that float holographically in space. Or they can don an array of body sensors in the motion capture area and run design procedures as a digital avatar in a virtual world.

CHIL’s motion sensing area. Photo: Lockheed Martin.

What is perhaps most interesting about CHIL is that most of its tools are just standard consumer devices many gamers are already familiar with, such as Facebook’s Oculus Rift headset. While the company’s engineers do some integration to get all the pieces to work together smoothly, Bolthouse noted that sticking with consumer-grade devices eases the learning curve for design review participants, and also costs less than building their own customized systems. “We want it to be as easy as possible to use,” he said.

Lockheed Martin has applied these VR and AR capabilities to the manufacturing process for both the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle and the GPS 3 satellite system. Two or three times a year the company conducts what Bolthouse calls “deep dive reviews,” where a team of design, manufacturing and safety engineers rehearse the buildup of the vehicles from start to finish. Hosted entirely in a virtual environment, the engineers assemble the thousands of parts in the same order they’ll be built on the production floor, trying to identify any issues or potential improvements. Bolthouse said engineers also run simulations focused on specific components a dozen or so times a year, experimenting with the most efficient ways to install harnessing or the propulsion system, for example.

For the future, Bolthouse is hoping to further build upon CHIL’s remote capabilities. Up until last year, you had to visit the lab based near Denver, Colorado, if you wanted to participate in design reviews. Now, the company has developed a network platform to allow anyone to connect to the VR system from any location. “That’s going to save us money for travel costs and time, and allow us to improve our designs at a faster rate,” Bolthouse said.

“[VR] is already pretty real in terms of the look and feel, but that performance is just going to improve,” he added. “We’re continually going to be pushing the envelope of how we can make that virtual world more representative of the real world.”