Latest News

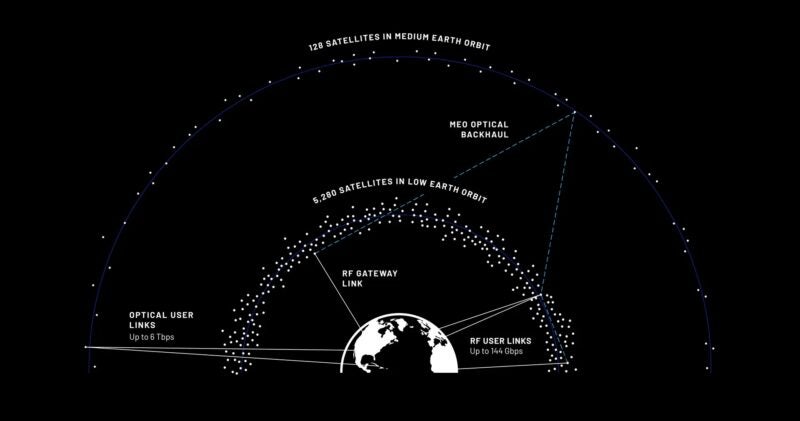

Blue Origin graphic on the TeraWave constellation plan. Photo: Blue Origin

Blue Origin is now targeting the satellite constellation market, in one of the biggest and perhaps even most surprising story of the year, Blue Origin announced it was going to build TeraWave, a new constellation of optically linked satellites in Low-Earth Orbit (LEO) and Medium-Earth Orbit (MEO), geared toward enterprise users and data centers. A satellite constellation is a new space venture for Blue Origin, which develops launch vehicles, engines, a lunar lander, and the Blue Ring in-space mobility vehicle. Given Jeff Bezos’s role in both Blue Origin and Amazon Leo, it is a fascinating development.

Via Satellite spoke to Alizée Acket-Goemaere, manager, McKinsey & Company; Caleb Henry, director of Research, Quilty Space; independent advisor Carlos Placido, Jean-Baptiste Thépaut, principal, Novaspace and Daniel Welch, CEO of Valour Consultancy, about the rationale for this move and how the constellation plans compare to others.

VIA SATELLITE: On a scale of 1 – 10, with 10 being very surprised, and 1 being not surprised at all, how surprised were you at this announcement?

Henry: I would say a five. Reusable rockets need significant demand to amortize their costs. Only SpaceX has demonstrated effective reusability, and that was only because Starlink provided sufficient internal demand. It’s not surprising that Blue chose the same route, only that it took so long.

Placido: We’ve already seen how SpaceX’s business has been transformed by Starlink through deep vertical integration across launch, satellite manufacturing, and network operations. With Bezos fully owning and controlling Blue Origin (as opposed to Amazon’s separate corporate structure), it’s not unreasonable to imagine a similar strategic ambition emerging over time. Having said that, the announcement was genuinely surprising to much of the industry, including myself. So I’d say around an 8. It could have been lower if Blue Origin were further along with big-rocket reusability, but they are clearly on that trajectory.

Thépaut: 9. We were definitely not expecting another Jeff Bezos-backed constellation in 2026, especially while Amazon Leo is still being deployed.

Welch: I wouldn’t say I was surprised as Starlink and Starshield has proven the appetite for this type of offering and so I’d been expecting competitors to emerge.

VIA SATELLITE: Blue Origin is positioning TeraWave as a more targeted, higher throughput service that would serve just around 100,000 customers total. Yet both TeraWave and Amazon Leo cite enterprise as a key vertical. Do you think TeraWave will be a competitor to Amazon Leo? Are you shocked that they could now be competing against one another?

Henry: The description Blue Origin put forward of TeraWave makes it clear they are striving to differentiate themselves from existing constellations. That said, broadband constellations take five to 10 years to operationalize, so TeraWave will be competing with the constellations of tomorrow, not today. By the time TeraWave is launched in appreciable numbers (and no, it won’t be 2027 or 2028, but the 2030s at best) they may very well compete with the constellations they hoped to outperform.

Placido: Based on what has been disclosed so far, TeraWave appears to be laser-focused (no pun intended) on enterprise and government use cases that demand ultra-high-throughput connectivity. The emphasis seems to be on middle-mile and backbone connectivity, path diversity, and resiliency rather than mass-market access. Amazon Leo, by contrast, will certainly serve B2B and B2G customers as well, but its core value proposition looks more aligned with last-mile and access connectivity, even if not exclusively so.

Given that framing, I don’t see TeraWave as a direct, head-to-head competitor to Amazon Leo. There will perhaps be some overlap in specific enterprise or government procurements they could end up competing. That said, the differentiation in scale, link speed, customer count, and network role should keep any internal competition manageable. So, it looks less like internal competition and more like complementary systems optimized for different layers of the connectivity stack.

Thépaut: I don’t really see Amazon Leo and TeraWave competing on the same verticals. TeraWave appears to be targeting use cases with very large capacity requirements and to rely on Q/V bands and optical links, which will materially affect both the form factor and the cost of user terminals.

This alone should create a natural separation between Amazon Leo and TeraWave, positioning TeraWave more as a competitor to O3b mPOWER, high capacity with large, expensive terminals, than to Amazon Leo and Starlink, which are optimized for lower maximum bandwidth with inexpensive, compact terminals.

VIA SATELLITE: What is your initial reaction to the architecture Blue Origin describes for TeraWave with 5,280 satellites in LEO and 128 satellites in MEO, all optically linked, as well as operating in the Q/V-band? What could this architecture enable in terms of services?

Henry: My initial reaction is that TeraWave will require a lot of new technology. The satellite industry has yet to normalize the use of Q/V-band, which means a significant amount of non-recurring engineering will be required for customer-ready equipment. Ultra-high-capacity optical terminals present another challenge, as they remain unproven outside limited demonstrations. Furthermore, symmetrical connectivity is not a hallmark of satellite broadband and won’t be easy to pull off. If realized the way Blue describes it, TeraWave could really offer ‘fiber in the sky’ type services. But there’s a lot of new technology needed to make that claim credible.

Placido: My initial reaction is that this is an ambitious, multi-orbit, multi-technology architecture that comes with moving parts, including launch capabilities and technologies that need to mature.

Optical crosslinks between satellites are now a proven capability, but TeraWave goes a step further by betting on both space-to-ground MEO lasers and LEO use of the Q/V-band. Those elements still present tech challenges, particularly around atmospheric effects and terminal availability, but they are exactly the areas the broader industry is actively working on.

While some satellite operators may view TeraWave as a competitive threat, I also see a significant upside in Blue Origin potentially accelerating the maturation and adoption of space-ground optical networking and Q/V-band operations at scale. In that sense, the broader ecosystem could benefit from the technological push.

Thépaut: I think the main challenge will be to demonstrate the network’s resilience to rain-fade attenuation.

While there are still limited details on the system architecture, one could envision TeraWave offering optical links to data centers with Q/V-band links as a fallback. However, for Q/V bands to be considered a credible backup, Blue Origin would need to convincingly address rain-fade mitigation, which does not yet appear to be a mature or well-proven capability.

Welch: When I saw the network will operate in the Q- and V-bands, my immediate reaction was to question how quickly the supply chain would be able to respond to produce the volume of associated user terminals to satisfy demand. 2027 is not far away and scaling up fast will be vital. Q-/V- bands are also more susceptible to weather, which is another area Blue Origin will need to provide reassurances to customers.

VIA SATELLITE: What do you see as the rationale behind this move?

Placido: SpaceX has clearly demonstrated the advantages of full vertical integration, and Blue Origin may be seeking a similar long-term position by pairing launch with downstream infrastructure. Amazon and Blue Origin are not vertically integrated, and given Amazon’s status as a public company, it’s not obvious that Amazon could (or would) sole-source launch services to a privately owned provider like Blue Origin.

Launching a constellation under Blue Origin also gives Jeff Bezos the ability to pursue a long-term, capital-intensive strategy with greater control and patience than would typically be possible inside a public company. The timing may be influenced by emerging demand for high-capacity, resilient data transport (potentially linked to defense and AI-driven workloads) where a multi-orbit, optically connected network could serve as foundational infrastructure.

Thépaut: I think Blue Origin has an interesting play here. They are not competing head-on with Starlink or Amazon’s Leo constellation, whose core business remains consumer broadband, nor are they directly competing with Eutelsat OneWeb or Telesat Lightspeed, whose value propositions are fundamentally different, centered on enterprise, mobility, and government markets, with relatively low-cost terminals and service-level agreements that would be very difficult to replicate in the Q/V bands or with optical links. In my view, TeraWave is targeting an entirely new market — one that has not historically been considered truly addressable by satellite systems.

Diversifying potential revenue streams could further enhance valuation, particularly if Blue Origin were to consider an IPO, allowing the company to capitalize on the current momentum in the space sector within the capital markets.

VIA SATELLITE: What do you think of the data center play?

Acket-Goemaere The biggest upside for space-based data centers is likely a post-2030 story. Demand for data storage and compute is soaring globally, driven in part by AI. Terrestrial constraints around power, land, and cooling are tightening and pushing operators to explore alternatives. Space-based data centers offer the potential to bypass some of these terrestrial bottlenecks and are moving from a purely experimental concept toward a more credible emerging theme, with early backing from both technology companies and space players, though the model remains far from commercial maturity. Significant challenges remain across physics, including radiation exposure, economics due to high capital intensity, and sustainability related to maintenance and servicing, which will likely constrain near-term deployment. In the near term, we expect more targeted use cases focused on accelerating existing space-based workflows, with the larger commercial upside more likely to emerge after 2030.

Henry: I’ve yet to form a substantive opinion on orbital data centers just yet. There’s a lot of hype, and it’s hard to clear the signal from the noise.

Placido: The data center angle may be part of the mix. MEO orbits could support space-based data processing and relay functions through ultra-high-speed optical links. I see the near-term opportunity less in fully fledged ‘space data centers’. Yet, optical links could enable secure, resilient data transport between cloud regions, and remote edge sites, something that would be highly attractive to large cloud operators like (you guessed it) AWS. TeraWave could become a useful tool in the toolkit of AWS, even if not directly integrated.

VIA SATELLITE: Do you genuinely believe there is this much demand for bandwidth for all of these constellations?

Acket-Goemaere Satellite broadband adoption has surged in recent years, led by residential connectivity, while mobility use cases such as in-flight and maritime connectivity are among the fastest-growing segments, signaling that satellite networks are becoming essential complements to terrestrial infrastructure. Total available bandwidth intentionally exceeds current demand. LEO constellations are designed to over-provision capacity in order to serve demand hotspots, even though satellites spend much of their orbit over regions with limited or no connectivity demand.

Demand dynamics vary significantly by geography. Markets such as New Zealand, with challenging terrain, low population density, and high purchasing power, have seen strong uptake, while in lower-income regions the upfront cost of terminals remains a major barrier to adoption.

One segment we expect to continue growing is enterprise connectivity, particularly for businesses operating in remote or hard-to-serve environments that increasingly rely on automation and data-driven operations. Across industries including agriculture, logistics, mining, construction, and energy, we estimate that there are roughly 100,000 off-site enterprises and up to 300 million small businesses globally, many of which could benefit from enhanced satellite connectivity, with pricing and service reliability as the primary levers shaping adoption.

Placido: I do believe there is significant potential demand, particularly given the likely emergence of an AI-driven ‘Digital Industrial Revolution’, which will create insatiable bandwidth needs for mobility, enterprise, and data-intensive applications, both inside and beyond terrestrial coverage. Demand is of course linked to price, and if Blue Origin succeeds in maturing the space-to-ground technology and deploying TeraWave at scale, satellite capacity pricing (especially for middle-mile or fiber-like backbone connectivity) could drop, which would in turn stimulate even more demand.

Thépaut: If we look only at existing customers, the answer is clearly no: the capacity that will be deployed by all NGSO constellations vastly exceeds even our most optimistic demand projections. Starlink appears to be betting on price elasticity of demand, aiming to make satellite connectivity cheaper than terrestrial alternatives for certain use cases. By contrast, TeraWave seems to be pursuing a technology-push strategy, betting that the availability of very high-throughput satellite capabilities will unlock entirely new markets.

Welch: In the context of a constellation the size of TeraWave, I believe the opportunity is limited to a very small number of players – perhaps 2-3. But there’s also growing evidence of appetite for smaller sovereign-owned constellations to improve resilience and control. Ultimately, demand is ramping up and customers have shown they are typically unprepared to wait, so all eyes are on which vendors can get satellites into orbit first.

VIA SATELLITE: Given the challenges that the likes of Amazon and Telesat have had when it comes to building constellations, do you think that Blue Origin will face similar challenges, or possibly similar delays when launching TeraWave? Do you think they will genuinely begin deploying satellites in 2027?

Henry: I think the challenges for TeraWave will be bigger than any other LEO constellation given the raft of new, low TRL features they anticipate wielding. Unless they started TeraWave years before the announcement, I don’t expect any material launches this decade, let alone 2027.

Thépaut: It seems reasonable to assume that satellite manufacturing will be done in-house and that Blue Origin would prioritize its own New Glenn launcher for TeraWave deployment. However, New Glenn’s manifest already appears heavily loaded, notably with 27 launches planned for Amazon’s Leo constellation, 5 launches for Eutelsat, and an as-of-yet undetermined number of flights expected for Telesat’s Lightspeed.

Welch: The timelines feel aggressive and history suggests delays are inevitable. What’s working in Blue Origin’s favor is that it has the funds and the launch vehicle.

VIA SATELLITE: Who (or which operators) should be most worried by this announcement?

Henry: I wouldn’t worry about Powerpoints and press releases. Yes, Blue Origin is a heavy hitter, but for now this is still a paper constellation.

Placido: I believe TeraWave’s disruption potential could put pressure on yet-to-launch B2B/B2G constellations like Telesat Lightspeed and Rivada Space, though geopolitical pressures to diversify away from U.S.-centric space businesses may provide them some resilience. The middle-mile and fiber-like capabilities of TeraWave also introduce new competitive challenges for operators like SES. That said, SES’s mPOWER is funded and operational, and European space sovereignty priorities may support SES in the medium term.

Thépaut: The most obvious candidate is O3b mPOWER, currently the go-to solution for high-capacity needs where terminal size and cost are less critical, covering large-capacity backhaul, trunking, and cruise ships. However, O3b mPOWER is limited to 10 Gbps per link and would be outclassed by TeraWave if the announced performance levels are realized.

Stay connected and get ahead with the leading source of industry intel!

Subscribe Now