‘SpaceX Effect’ Fuels Efficiency Push in Launch Services Market

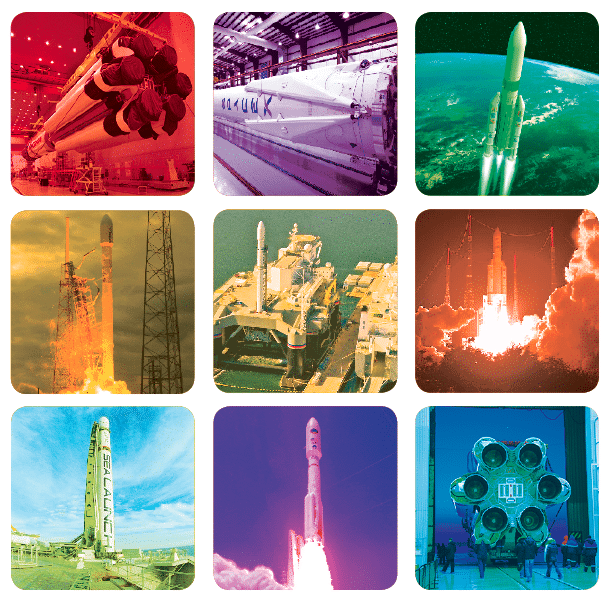

Satellite launch services providers are re-examining vessel management, engine design, and diversity of manifests, among other strategies, to lower costs and remain competitive. We take a deeper look at how each of the key players in the market is strategizing for future challenges.

It’s a busy time for the satellite launch industry if one goes by numbers of planned launches in the next few years. With an estimated 100 commercial satellites heading into low or medium-Earth orbit in the next three years by major MSS providers, Iridium, Orbcomm and Globalstar alone, the market’s prospects in the near-term are very positive.

“Over the next two to three years, I expect healthy, upward growth,” predicts Marco Caceres, senior analyst at the Teal Group. He adds that, as the wave of MSS constellation replenishments end, that segment will slow. The number of geostationary (GEO) satellites launching, however, will remain in the upper 20s in any given year.

Caceres, who moderated a panel on the satellite launch market during SATELLITE 2014 in March, anticipates more micro, nano and picosatellites going into orbit. This, however, will not translate in an increase in the number of actual launches since 20 or 30 of these tiny payloads can launch on a single rocket, he says.

Rachel Villain, principal advisor for Euroconsult, predicts that the market will remain stable in mature space countries such as the United States, Europe, Russia and Japan, and that it will grow in emerging space countries, including China and India.

Caceres agrees, noting, “There’s still a lot of areas in the world that don’t have basic telephone or TV service, so there is still going to be a lot of satellites for launch in new countries like Nicaragua and Ecuador — countries that are relatively poor but will have access to financing primarily through China and possibly Russia,” he says.

The one constant, adds Villain, will be continued fluctuations in price of launch. “Price variations over time are a constant of the commercial launch industry driven by the balance between launch supply and launch demand.”

She predicts that at least for GEO commercial launches, the difference in price points among providers will reduce in the coming years.

These days, cost of launch is all the industry can talk about after SpaceX rocketed its Falcon 9 to the International Space Station (ISS) in May 2012, and shattered the industry’s notion of affordable space access. It got NASA into orbit at approximately half the price tag of competing providers. Additionally, this past December and January, SpaceX launched its first two commercial GEO missions on a new, more powerful version of its Falcon 9 rocket.

“The model everyone is looking at is SpaceX — how is it that they can offer a fairly reliable vehicle so quickly and roughly 50 percent cheaper than companies like Arianespace, Boeing, Lockheed and even the Russians?” says Caceres. “SpaceX is making everyone aware that, if they want to be viable competitors in this market over the next five to 10 years, they’re going to have to find a way to radically reduce their costs and make their vehicle much more competitive.”

According to Villain, established launch service companies such as Arianespace and ILS will need to adapt to this market by offering lower prices for small satellites for Ariane 5, and dual launches of electric satellites for Proton. “The biggest hurdle,” she adds, “is to cut production and operational costs while maintaining reliability, both of the launch itself and of the launch schedule.”

Regardless of whether Elon Musk’s feisty start-up can maintain such a disruptive price point and keep up reliability as its fleet tackles larger and more complex missions is anyone’s guess. But, one point is indisputable: the “SpaceX effect” has ushered in a new era of cost-effective access to space, which is spurring changes in business models for the industry.

As Via Satellite examines the state of the launch services market, industry leaders are making hefty investments in dual-launch capabilities and reusable engines, among other moves, that they believe will bolster their fleets’ capabilities and efficiency, while ensuring their business’s viability in the future. Here’s what they told us.

Arianespace

Arianespace’s new CEO Stéphane Israël recently spoke to Via Satellite about his long term plans for the company. The world’s first commercial satellite launch company, Arianespace, continues to be Europe’s space launch backbone, which is expected given that it is owned jointly by the French space agency CNES, Airbus and other European space companies, representing 10 European countries in total.

By the second half of 2015, Arianespace intends to increase its payload volume beneath the Ariane 5 heavy-lift launch vehicle’s ECA fairing without incurring any performance loss. With 12 launches planned for 2014 if the satellites are available, Arianespace officials admit that they are preparing for an unprecedented level of activity, featuring different launchers. In the last year, the company has cut the time between launches of two different systems from three weeks to two, and more improvement is expected. “Our target is to work with six Ariane, three Soyuz and three Vega,” says Louis Laurent, SVP of programs at Arianespace.

To accommodate more launch volume, the company says it will finish construction of a new propellant loading hall at its Soyuz Launch Complex in the Guiana Space Center by early 2015. This center will give Arianespace three propellant loading halls fully available to customers, instead of the two current ones, explains Israël.

The company is also pursuing a dual-launch strategy. When Ariane 5 ME enters service in 2018, it will have higher performance and a larger payload volume. The new rocket will feature a re-ignitable upper stage engine, and will allow for the pairing of a large satellite of 6.5 tons with a medium one of up to 5 tons, instead of a large satellite with a small one, which is the case today.

“Our assumption is that the future launcher should be competitive both for small, medium and big satellites because we expect a balanced mix between these categories of satellites thanks to the penetration of electric propulsion. Dual launch should be considered for small sat,” concludes Israël.

Sea Launch Commander, Odyssey Launch Platform and Zenit 3SL rocket at the home port facility in Long Beach, Calif.

Photo: Sea Launch

Sea Launch

Serguei Gugkaev, CEO of Swiss-owned Sea Launch, spoke to Via Satellite soon after his company celebrated the 15th anniversary of its first maritime launch in 1999. In 2016, Gugkaev plans to celebrate another milestone: the first dual launch in Sea Launch history carrying the AngoSat 1 and Energia 100 satellites.

“One of Sea Launch’s operational benefits is our relatively small, flexible launch pad — we have fewer people supporting the launch,” says Gugkaev, noting that having fewer people has allowed the company to reduce fixed costs during periods of less launch activity.

Sea Launch’s reliance on an ocean-based launch system, however, presents important challenges: from having to manage sea conditions that can jeopardize launch schedules, to rising fuel costs that can drive up expense of transiting the vessels to and from its equatorial launch site. “We need to continue to refine our launch operations while increasing the system’s overall reliability,” says Gugakaev of his these challenges.

One key initiative is to introduce aerospace quality standards, such as EN 9100 certification for flight hardware, to the company’s Russian and Ukrainian suppliers, which he believes will improve the reliability of their launchers. Currently, 90 percent of their flight hardware is Russian/Ukranian made, but Gugakaev hopes to open up Requests for Proposals (RFPs) for parts of their rocket to more suppliers, thereby getting better pricing. “We are welcoming competition in the procurement area,” he says.

ULA’s Atlas 5 rocket carrying the NROL 67 spacecraft from Space Launch Complex-41 at Cape Canaveral, Fla. Photo: ULA

United Launch Alliance (ULA)

Denver, Colo.-based United Launch Alliance (ULA), the Lockheed Martin and Boeing joint venture, enjoys an enviable legacy of shepherding the U.S. government’s launch programs for the last five decades, a position that gives the company its great strength of experience, but also possibly its greatest handicap — high operating costs from having to build and maintain two independent launch systems for the U.S. government.

“In the past the government told us, ‘we want that redundancy; we want you to maintain it.’ Now they’re saying ‘be competitive, be lower cost,’” says George Sowers, VP of strategic architecture for ULA, referring to the mandate the entity had when it formed in 2006 to provide assured access to the U.S. government with two independent launch products: the Atlas and the Delta.

The company is looking at efficient ways to dispose of its upper stages among other initiatives. “We understand that there is a lot of downward pressure on prices right now and we are looking at technologies that enable us to lower our costs, particularly in the propulsion world,” Sowers says, admitting that the new low-cost priority coming from the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) is requiring ULA to rethink its business at a fundamental level.

Currently, the company is deploying a new set of avionics that be shared on both the Atlas and Delta vehicles, a move that will lower cost because it will increase their production rates. Longer term, Sowers isn’t ruling out getting down to one vehicle. “It won’t happen overnight, but that certainly will be the end state that we will be looking for,” he said.

Looking out five years, Sowers anticipates that national security demands will diminish “because of budget constraints and other factors.” This is prompting ULA to look at other businesses. Currently, the company is on two of the three teams competing for NASA’s commercial crew program.

“We’re on the Boeing team and the Sierra Nevada team. We’re going through critical design reviews for the technology that is required to fly humans on Atlas,” Sowers says. One change involves developing an emergency detection system to monitor the health of the rocket in flight and to give the crew the ability to abort the mission if there is a problem.

NASA will award the winner(s) in August. Since the United States has decided to maintain a station on the ISS through 2024, “we see missions to the ISS as a nice anchor tenant business for us to have,” Sowers says. “We expect to continue to be the workhorse vehicle for NASA science, but we are also looking to re-establish a bigger presence in the traditional commercial market.”

Sowers says that Atlas has enjoyed a long history of commercial service, launching both Inmarsat and SES satellites. “What we need to do now is re-establish those relationships and start getting back into that market,” he added.

International Launch Services (ILS)

John L. Palmé, vice president and chief technical officer for International Launch Services (ILS) says his company is evaluating the technical feasibility of launching two large satellites at the same time on a Proton Breeze M launch vehicle.

“In recognition of the increased market interest in lower mass, electric or hybrid propulsion spacecraft, we are actively marketing Proton’s dual launch capability,” he says, explaining that with a dual launch on Proton, customers can cost effectively launch smaller stacked satellites to various orbits — either GTO or GSO or a combination of the two. “Dual launching reduces the cost to orbit, with Proton launching two stacked satellites for the same price as a dedicated single launch. This means we could launch two electric propulsion satellites of three or more metric tons each.”

According to Palmé, a dual launch would be ideal for smaller spacecraft like the Boeing 702SP, “which would have the advantage of decreasing the orbit raising time from months to weeks.” He explains that ILS will be able to generate revenue earlier and avoid the risk associated with the Van Allen Radiation Belt.

Palmé adds that the availability of export credit financing will be especially helpful to operators who otherwise would not have access to low cost financing.

“There have been significant developments that have taken place with Export Insurance Agency of Russia (EXIAR) financing over the last year. Several major international banks have completed or are completing their due diligence process of the EXIAR offering. “ILS introduced EXIAR to many of our customers in 2013 and we are actively pursuing this market with our customers. There are several advantages to an EXIAR credit guarantee over those offered by Coface [and] ExIm Bank, which will greatly improve the Proton value proposition for our customers,” he says.

SpaceX

Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s president and COO, echoed other industry players in the value proposition of reusable engines, noting that, on a recent cargo resupply mission for NASA, SpaceX successfully returned the Falcon 9 first stage from space. “We’re targeting return of a Falcon 9 first stage to land as early as the end of this year,”

she says.

SpaceX has a dual path of development and testing with existing missions, as well as testing in Texas and New Mexico on a flight-like development platform (F9R). Currently, the company is evaluating locations for its new commercial launch site, which Shotwell says is expected to break ground later this year.

SpaceX also is converting Pad 39A, the former shuttle pad in Cape Canaveral Florida, into a launch site that will support both Falcon Heavy launches as well as future Dragon crew missions, according to Shotwell. “SpaceX has invested heavily in the ramp up and expansion of our production facilities with the ultimate goal of producing 40 cores per year, supporting two launches each month from each of our sites,” she adds.

The company currently has nearly 50 missions on its manifest including a combination of U.S., commercial, international and government customers. However, Shotwell insists that this diversification is not a factor in SpaceX’s low pricing. A Falcon 9 launch is currently priced at $56.5 million while a Falcon Heavy launch runs $77.1 million for up to 6.4 tons to GTO. The price jumps $15 million for greater than 6.4 tons to GTO.

While the company “offers the same pricing to all customers,” Shotwell cautions that government customers’ “non-standard technical, procedural and reporting requirements” could drive up the baseline cost.

As all these companies reposition themselves in a rapidly evolving market, one thing is clear: the next few years will be anything but dull.

The Fight for Fair Market Competition

In the United States, the land of entrepreneurial dreams and free market economies, the launch industry is anything but open. United Launch Alliance (ULA), the 50-50 venture of Lockheed Martin and Boeing, is currently the only provider certified to launch the DoD’s critical national security payloads through the Air Force’s Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) contract.

The Air Force’s original intent for the EELV back in 1995 was to reduce the cost of operational space launch by 25 to 50 percent, improve reliability over the heritage launch system, and to create a more “commercial-like” procurement process. Initially, Lockheed and Boeing were competitors, but in 2006, the two companies formed ULA, asserting the entity would save U.S. taxpayers around $100 to $150 million per year — savings that never materialized.

ULA was awarded the most recent multi-billion-dollar, five-year EELV contract for rocket boosters and launch services in June 2013. By 2030, spending on the program is expected to reach $70 billion.

SpaceX has been the only entrant to get close to going after ULA’s dominant position, with its winning of the NASA cargo-refueling contract for the ISS and its attempt to meet the Air Force’s certification requirements to compete for the EELV contract. The company’s certification has been in the works for months and the Air Force recently stated the certification could be complete by March 2015.

For its part, the Hawthorne, Calif., startup isn’t taking the latest setback lying down. At press time, it was pursuing a federal suit against the U.S. Air Force, claiming procurement officials deliberately delayed awarding SpaceX’s certification, effectively shutting the younger company out of competing for the lucrative contract. The suit also criticizes ULA for using Russian engines in some of its rockets, which SpaceX contends is a violation of U.S. sanctions against Russia. The company has gotten the ear of influential members of Congress as well as a U.S. Court of Federal Claims judge, who issued an injunction to prohibit ULA from proceeding with plans to buy Russian-made rockets. Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder, has made an argument that the latest launch contract “should be competed.”

In a public statement issued on April 29, SpaceX noted that since ULA came into being in 2006, “vehicle costs are up from approximately $100 million per vehicle to $400 million per vehicle—making ULA’s launch vehicles the most expensive, not just in the United States, but the world. In addition, the United States pays ULA nearly $1 billion dollars per year just to maintain the ability to launch — regardless of whether or not they launch a single rocket. The EELV program is now the fourth-largest line item in the country’s entire defense budget.”

Jessica Rye, spokeswoman for ULA, contends that the recent five-year block buy contract has enabled the government to negotiate a block of launches in advance that will provide “significant operations efficiency and create the needed stability and predictability in the supplier and industrial base, while meeting national security space requirements.”

ULA also stated that the multi-year investment will save the government and taxpayers “approximately $4 billion while keeping our nation’s assured access to deliver critical national security assets safely to space.”

Any new entrant must meet rigorous certification criteria of vehicle design, reliability, process maturity and safety systems in order to compete, “similar to the process that ULA’s Atlas and Delta products and processes have met,” Rye stated.

The United States isn’t the only market perceived as closed. In Europe, Arianespace continues to receive subsidies from the European government.

“[Arianespace is] a consortium — they have a great vehicle — but if you look at their profits and revenue over the last 10 years, they are barely able to make a profit in a year when they are already getting a subsidy,” says Marco Caceres, senior analyst at the Teal Group. “If they were not getting these hefty subsidies from the European government, they would never be profitable.”

Caceres says that even ILS’s Proton launch vehicle was developed under the Soviet economy in the 60s and 70s. “No company out there competing in the commercial launch market is truly a commercial company except probably SpaceX,” he adds.

Arianespace’s chief executive, however, defended his company’s improved competitiveness during an audit in the French Accounting Court in February. Since 2005 Arianespace has cut by half the $273 million in annual subsidies it receives from the European Space Agency (ESA). In addition, the reliability of the Ariane 5, which has seen 58 consecutive successes since 2002, has enabled the company to increase launch prices. And, during that same audit, Arianespace highlighted the fact that SpaceX benefits from a weak dollar and a huge contract with NASA to go to the ISS.

Even with these efforts, analysts remain skeptical of the market’s reliance on subsidies changing anytime soon. Asked if there will be more of a level playing field and less government support of launch providers going forward, Rachel Villain, principal advisor for Euroconsult, expresses doubt. “Not likely if the governments remain the number one client of the launch vehicles for which they have paid for development,” she says. VS