How Space-Based Data Enables the Climate Solutions Posed By COP-27

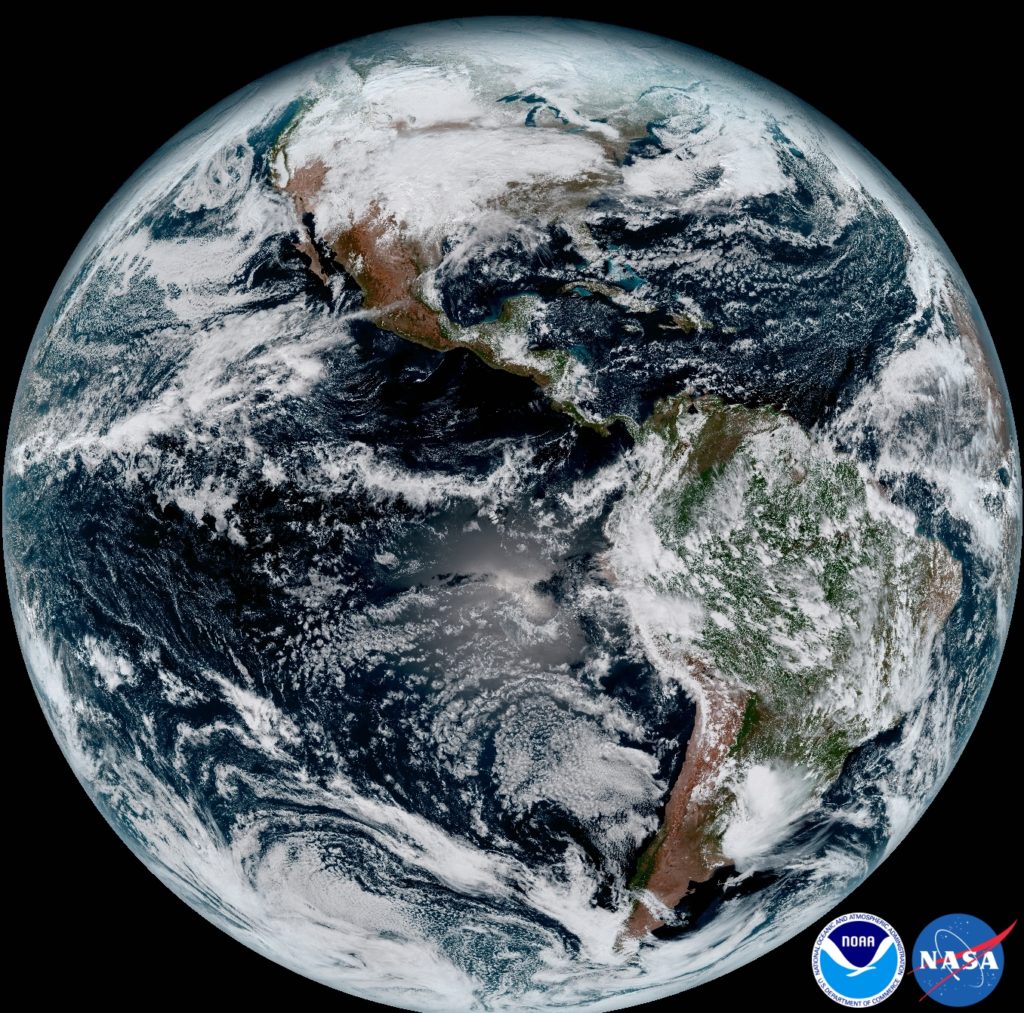

Composite color of Earth capture by GOES-16. Photo: NOAA, NEDSIS.

Held in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, COP-27 came with its lot of successes and disillusions, among which a lost opportunity to address the pressing issue of curbing the use of fossil fuels. Yet several advances now point towards a greater collaboration between rich and developing economies, and just as it has always been at the rendez-vous of the fight for climate, the space sector is more than ever a key to some of our future common successes.

While many nations had space capabilities displayed in their COP27 pavilions, the sector was notably the subject of The Patterns of the Past – The Promise of Tomorrow, a film shown that made the headlines by showcasing the contribution of Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellites to climate change monitoring, notably by feeding the Australian and African respective Digital Earth initiatives.

Of the main advancements reached following COP27 discussions, two climate action implementation mechanisms stand out: The announced Loss & Damage Fund and the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage. For both, satellite technologies can be anticipated to be key enablers in the years to come.

A first milestone, the Loss & Damage Fund is expected to provide countries vulnerable to devastating climate impacts (i.e. floods, droughts, hurricanes and sea level rise). The fund, of an amount and organization that is to be decided by a transition committee leading to COP28, is expected to financially support countries who suffer from climate disasters while also providing funding for adaptation to the challenges of climate change.

One can easily see where space data will fit in the picture. By providing actionable insights, Earth observation imagery and value-added services data will help measuring structural, environmental and societal damages incurred by vulnerable countries helping them make a concrete case for compensations they will seek via the Loss & Damage Fund and prompting timely and efficient responses from funders. This, in turn, will facilitate traceability of the funding channeled, reassuring donor countries and the future chairing committee on the concrete use of unlocked funds.

Some of the foreseeable use cases and insights are typical of what satellite imagery is now used to providing. Think of change detection for example, to quickly identify damages delt to public infrastructures following catastrophic events or the emergency response and disaster risk management capabilities that the European Copernicus program is now used to delivering for its partner countries. Think also of the contribution of satellite imagery to the management of coastal areas, the monitoring of biodiversity and the management of forests and deforestation via initiatives like REDD.

But space technologies will not only contribute to the delivery of insights and we can also expect, or at least wish, they will be at the core of the technical assistance that will be channeled via the second major outcome of COP27 that is the operationalization of the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage (SNLD) initiative, priorly agreed upon during COP26. It is known that for countries that lack a space legacy, the use of space assets as an agent of change can be complex. Access to space infrastructures is not trivial with the most vulnerable countries to climate change often not owning their own satellite systems, thereby having to rely on assets owned by other countries to access satellite imagery, and sometimes lacking proper IT infrastructures to store, analyze and disseminate it.

But the proper use of satellite-based insights is also complex as countries need a properly trained workforce to analyse geospatial data and perform complex data-fusion operations. This is where we can expect the SNLD to come into place. The international community has long anticipated the difficulties in accessing space assets and data insights. Copernicus data for example is widely disseminated in the African continent through initiatives like the “GMES and Africa” cooperation that disseminates more than a petabyte of EO data yearly. But the SNLD can now provide a new framework via which space-based technical assistance can be channeled, taking the form of either a greater access to satellite capabilities and dedicated imagery or the training of an entire new generation of geographic information system (GIS) skilled workforce. Overall, this additional support can be expected to improve and fasten vulnerable countries’ responsiveness to climate change, leading to reduced socio-economic vulnerabilities.

Satellites technologies were also brought under the spotlight following the United Nations announcement of a Methane Alert and Response System dubbed MARS. MARS bears the objective of constituting a public database of satellite data based global methane leaks detections, one that will be made public in order to nudge companies and governments into curbing methane emissions or else face potential public backlash. This announcement comes at a time of great focus by the space community on Methane emissions, one of strongest climate change greenhouse gas (GHG) contributor.

While several institutional satellite programs like Copernicus Sentinel 5P and its TROPOMI instrument started tracking methane emissions a couple of years ago, they are now complemented by higher resolution satellites from non-profit organizations, like the future MethaneSAT of the U.S. Environmental Defense Fund, and most recently by corporate ventures like GHGSat that plans on sending a small constellation capable of tracking methane leaks. The UN’s MARS initiative therefore illustrates how international institutions and corporate ventures can now work hand in hand in tackling climate change with both technological and diplomatic initiatives.

Whether encased in international cooperation frameworks or as part of space nations’ national efforts, space is increasing its grounding as an indispensable agent of the fight against climate change and its impacts, and much can still be expected from the sector in the years to come. The recent announcements of French president Emmanuel Macron to organize a dedicated summit for climate change and developing countries in June 2023, prior to COP28 to be held in Dubaï, will most certainly be another opportunity for space to assert its decisive role.

Mathieu Luinaud is a manager in strategy consulting within the PwC Space Practice and a senior lecturer in Economics at Sciences Po Paris. His experience covers space domains from upstream to downstream. He has worked extensively with satellite manufacturers and satellite operators on business model development and market assessments. He is a member of the International Institute of Space Law (IISL) and currently serves as deputy-mayor for Paris 15th district.

Mathieu Luinaud is a manager in strategy consulting within the PwC Space Practice and a senior lecturer in Economics at Sciences Po Paris. His experience covers space domains from upstream to downstream. He has worked extensively with satellite manufacturers and satellite operators on business model development and market assessments. He is a member of the International Institute of Space Law (IISL) and currently serves as deputy-mayor for Paris 15th district.