How Will the US Government Respond to a Space Weather Emergency?

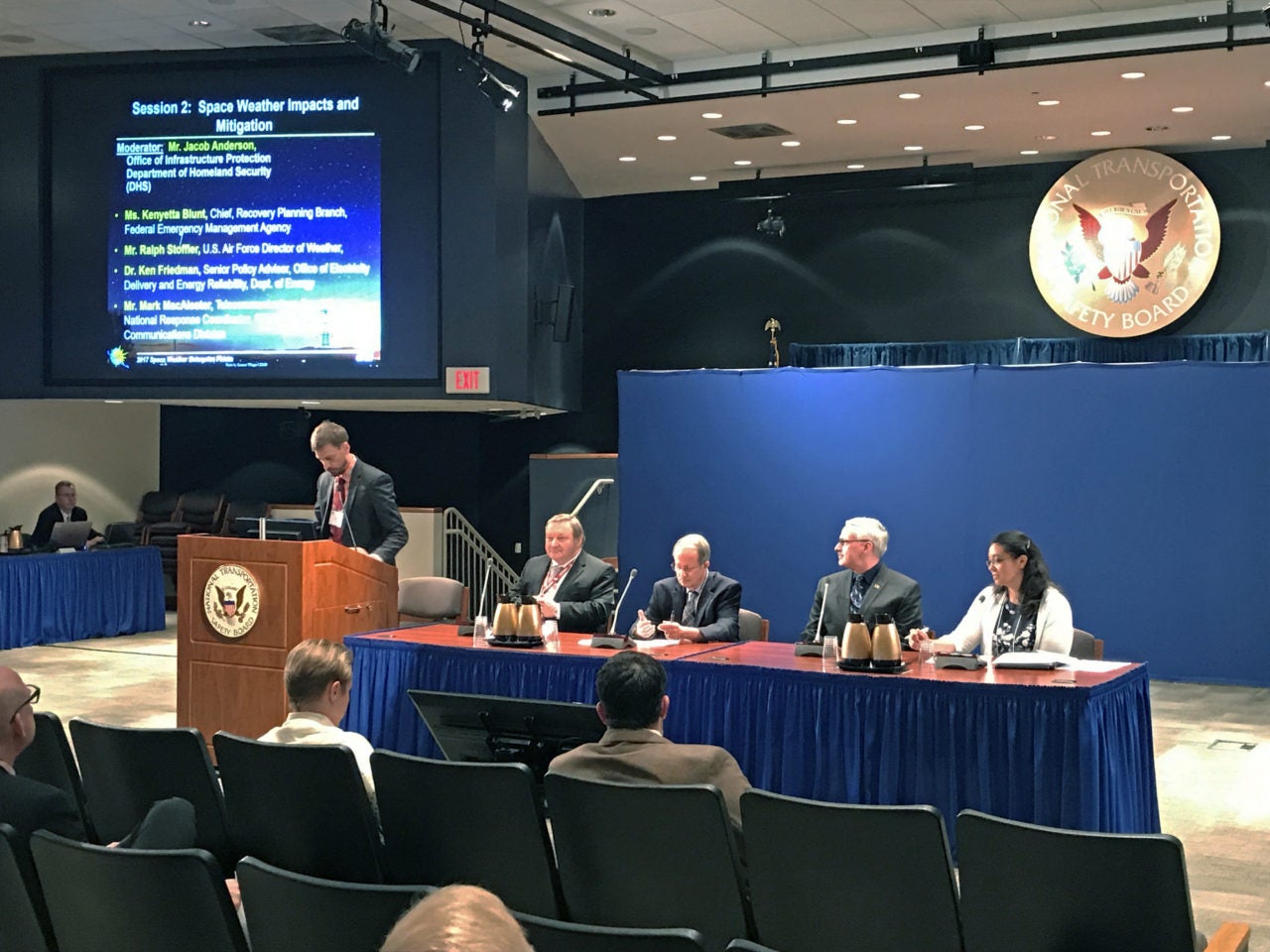

From L-R: Jacob Anderson, Office of Infrastructure Protection, DHS; Ralph Stoffler, director of weather, deputy chief of staff for operations at US Air Force; Ken Friedman, senior policy advisor, Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability, DOE; Mark MacAlester, national response coordinator, Disaster Emergency Communications, FEMA; Kenyetta Blunt, chief of Recovery Planning Branch, FEMA.

In one of his final initiatives as President of the United States, Barack Obama introduced an executive order coordinating efforts to prepare the country for space weather events. Since its signing, government organizations such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Department of Defense (DOD) have collaborated to reconstruct their strategies and put forth a more comprehensive response plan in the event of a significant solar anomaly.

At the Space Weather Enterprise Forum in downtown Washington, D.C. this week, Mark MacAlester, national response coordinator for FEMA’s disaster emergency communications division, identified geomagnetic storms as one of the most potentially damaging threats. A geomagnetic storm is a disturbance in the Earth’s magnetosphere following a solar wind shockwave, usually generated by coronal mass ejections or solar flares.

“The biggest thing we worry about here is the L-band will be severely impacted in this kind of event,” MacAlester said. He explained that while higher frequencies are less affected by geomagnetic storms, L-band, which notably is where GPS receivers operate, is particularly susceptible. “L-band is critical. Anyone who has used a satellite phone has probably used an L-band device,” he said.

Due to such threats, Kenyetta Blunt, chief of FEMA’s recovery planning branch, stated one of FEMA’s first objectives was to develop what is known as the Power Outage Incident Annex (POIA). Formulated in the wake of Superstorm Sandy, POIA dictates how the federal government will react to wide-scale power outages. “The current plan and process we had in place to manage long-term power outages was not sufficient,” Blunt said during the forum.

One of the biggest challenges for the federal government, she said, is that it does not manage its own power lines or companies. Thus, in the event of a disaster, the federal government cannot restore power itself and can only provide ancillary support to utility companies during the aftermath — and only if they request it. “We have to wait to be asked to provide this assistance,” Blunt said.

U.S. utility companies are certainly no stranger to major outages, particularly in the Southeast region of the country where hurricanes are most prevalent. However, even major storms such as Katrina have only knocked out power for a couple of weeks at most. Moreover, the impact range of a hurricane is relatively small compared to a potential outage caused by a major solar event.

“If, for instance, the whole East Coast was impacted by a large power outage, it would more difficult for people to up and relocate,” Blunt said. “We never thought beyond what would happen if it was a population of 2,000 [affected]. 200 million is significantly different.”

And while most communities can be fairly resilient during a power outage for about a week, situations can quickly turn south without the ability to refuel generators after an extended period of time, Blunt pointed out. “Getting people to think beyond the normal week or two weeks you see with a bad storm was the challenge,” she said. “There were a lot of agencies that were not capable of doing that.”

Now, though, Blunt said FEMA has begun partnering with entities in the energy sector to streamline the emergency response process, which includes enforcing road closures and coordinating debris removal to give companies access to the areas most impacted. FEMA is also in the process of developing a Concept of Operations Plan (CONPLAN) that will address how each government agency should react in response to a space weather event, as well as select a singular entity that all other agencies would report to. Blunt said further details on the plan should emerge in the coming weeks.

Ralph Stoffler, director of weather and deputy chief of staff for operations at the U.S. Air Force headquarters, noted that DOD also has a vested interest in bolstering resilience against space weather. “When you’re flying a bomber at a high level, you need to have long-range comms. You have to be able to find your target, hit your target and only your target,” he said. If GPS communications are inaccurate or offline, a military operation could inadvertently cause loss of life. “Anytime civilian casualties take place it’s a big deal. We try to minimize that by providing very accurate strikes. GPS and satcom is critical to making that happen,” he said.

To ensure its operational datasets are robust, DOD and other agencies are reaching out to both academic researchers and the commercial sector to provide their data, as well as government agencies from foreign allies such as Canada. “We can’t do it alone. Integration and cooperation with everybody out there is where we need to be,” Stoffler said.

Generally speaking, we’ve become very good at predicting when hurricanes, thunderstorms and other severe terrestrial weather will strike and what their impacts will be, Stoffler said. “We need to reach the same level with space weather because the impacts are out there and they’re a lot more subtle,” he concluded.